How To Make Smart Mistakes

You screwed up, and you know it. Here’s why you should be ecstatic, plus what to do next.

As we grow up, we are programmed to fear making mistakes.

Recently, it’s become fashionable to embrace them.

The truth is somewhere in-between.

First things first. A little fear of making a mistake is good. It pushes us to be thoughtful and make smart decisions. However, inflate that same fear just a bit and it can lead to stress and, worse, paralysis.

Oh no.

Oh no.

To handle mistakes successfully, we need a structured approach to processing and learning from our mistakes. Then we need the strength to forget all about them.

Don’t Worry, Be Happy Now

So why should you be happy that you screwed up and know it?

Because “knowing it” means you’ve identified that you have a problem and have at least a vague sense of the issue. That means you are already headed in the right direction.

What You’ll Learn

Here are some examples of what we’ll cover in this article:

- Why your response to the mistake is so important

- How to break a mistake down and decide how much effort to invest in preventing it from happening again

- The 5-part guide to surfacing the details of your mistake so you understand how to avoid it in the future

The Seven Rules of Making Mistakes

- Try (pretty hard) to avoid mistakes

- If you’re not making any mistakes, you’re not stretching yourself

- Almost all mistakes are due to the process and not the person

- Not all mistakes will be evident to you

- How you react to a mistake is usually what matters

- Know when to invest

- Mistakes are a learning opportunity, then they are baggage

Rule 1: Try (pretty hard) to avoid mistakes

This one should probably go without saying but is important to state at the start. Put in the effort. Do a good job. Your goal is to avoid mistakes.

But don’t let a fear of making a mistake paralyze you. Instead, accept that you will make mistakes in life, and your reaction to them says more about you than their occurrence does.

Rule 2: If you’re not making any mistakes, you’re not stretching yourself

Despite rule #1, we know mistakes will happen. One way people minimize errors is by sticking to doing what they’ve always done before. Maybe stagnation is okay with them — if so, great.

But if you want to grow, be prepared to make mistakes — You’re trying new things and getting out of your comfort zone. Generally, the newer those things are, the bigger the slips will be. And those mistakes will teach you what not to do in the future.

So instead of trying to avoid mistakes, consider being smart with your mistakes.

How? Take more risks in areas with higher upside and lower downside.

Choosing To Make Smart Mistakes

There are two dimensions of risk that are paramount when aiming to make smart mistakes.

- potential impact of the mistake vs upside result if all goes well, and

- probability of making the mistake vs everything going smoothly

By considering the choices you make along these axes, you can see which risks to take by targeting options where the potential upside result of success is worth the probability and/or potential impact of making a mistake.

Some examples:

Experimenting with a new daily routine is a SMART risk to take

Best case scenario: you’re a bit more productive every day for the rest of your life.

Worst case scenario: you’re slightly less productive for a day or two.

Potential upside impact: Very High

Potential downside impact: Low

Likelihood of success: Moderate-to-high

Likelihood of failure: High-to-moderate

Well the likelihood of success may not be very high, experimenting with a new daily routine has small potential downside impact with very high potential upside impact. Even if it takes a dozen experiments or so, the potential accumulated advantage wins out.

Not wearing a seatbelt is NOT a smart risk to take

Best case scenario: you save 6 seconds.

Worst case scenario: you’re dead.

Potential upside impact: Miniscule

Potential downside impact: Catastrophically High

Likelihood of success: Moderate

Likelihood of failure: Moderate

Are there some people who don’t wear a seatbelt and never suffer major consequences? Sure. But looking at the potential downside impact vs the upside makes it clear that this is a terrible place to risk making a mistake.

Mistake Budget

The engineers responsible for keeping Google up and running know that errors are going to happen sometimes. They also want to innovate as much as possible while keeping those errors to a reasonable rate.

They and other engineering teams have developed the idea of the Error Budget. The Error Budget essentially quantifies the relationship between the number and size of mistakes the team has made recently so that they can understand the acceptable level of risk to take moving forward while avoiding customer unhappiness.

It is significantly harder to quantify our personal mistakes, but still valuable to consider the type of risks we are taking and the potential impact on our own happiness and that of those around us.

Rule 3: Almost all mistakes are due to the process and not the person

When you make a mistake, it’s not because you are a failure or a terrible person.

(Side note: you might be a failure or a terrible person, or you might be the bestest person who ever lived. The point here is that mistake-making is unrelated.)

Almost all mistakes happen due to a problem with the process used and not because of the individual involved. And that means you can fix the problem by investigating that process and correcting it.

In engineering, we use what we call a blameless post mortem (though I prefer the term blameless retrospective in any case where the patient isn’t dead). The philosophy here can be applied to personal mistakes too.

Starting with the assumption that mistakes stem from the process and not the person encourages honesty about what went wrong and what steps you need to take to avoid a recurrence.

Rule 4: Not all mistakes will be evident to you

Some mistakes will blow up in your face. Those should be pretty obvious.

For example, if you’re a programmer and you just made a change in your code and your app breaks, you get a nice little error code (or an angry manager, depending on the maturity of your DevOps process).

But many mistakes conceal themselves. They might be small mistakes that accumulate over time, like overeating or avoiding exercise. Or they might just be subtle enough that they don’t come to your attention unless you take the time to look back and aim to identify them.

To be clear, many mistakes that are not obvious are small enough to be ignored entirely. But some hidden mistakes can affect the course of your life unless you take action. More on these “Level 3 mistakes” later.

Identifying those hidden mistakes that are important is essential.

Rule 5: How you react to a mistake is usually what matters

You know mistakes happen. I know mistakes happen. Most people understand and appreciate that mistakes happen.

In most cases, your reaction to the mistake will be much more memorable in the end than the mistake itself.

Identify the root cause. Communicate with anyone impacted. Determine what you can do to mitigate the consequences. Finally, come up with a plan to prevent this mistake from happening again. When thinking back on the incident, the speed and thoroughness of your response should be the narrative.

If others are involved, being upfront and honest about what happened will be better in 99% of cases than trying to cover up a mistake and pretend like it didn’t happen.

Rule 6: Know when to invest

You don’t have time to invest in avoiding every possible mistake. Even if you did, it would mean never doing anything. (As addressed in Rule #2.)

To prioritize and figure out how much time to invest in avoiding a mistake, we can categorize them based on their potential impact.

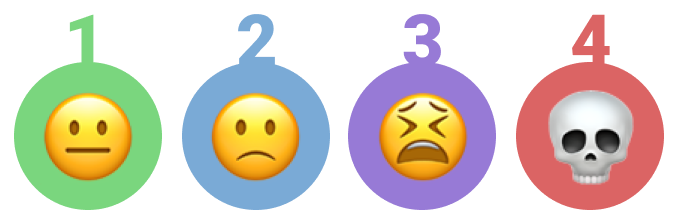

The Four Levels of Mistake Impact

The Four Levels of Mistake Impact

- Mistakes that have little impact each time and don’t accumulate impact if they recur

- Mistakes that have little impact each time but accumulate impact if they recur

- Mistakes that have a major impact if they happen once

- Mistakes that have an existential impact if they happen once

Level 1 Mistakes: NBD

Summary

Level 1 mistakes don’t have a major impact even when they occur repeatedly. These are not a big deal.

Example

You misspell some words as you type but auto-correct fixes them.

Awareness

You’re probably not aware of a lot of Level 1 mistakes you’re making. In the case of misspelling words, you may not even notice as your computer fixes them for you automatically.

Note that the auto-correct tool has moved this mistake (mistyping) from a Level 2 to a Level 1. Before auto-correct, if you were an office worker who regularly misspelled words, it would eventually reflect poorly on your employment. With auto-correct, not really a big deal.

Investment

Level 1 mistakes that are brought to your attention can be dangerous. Not because you need to spend time on them, but precisely because you don’t. They will take too much of your time. Generally speaking, Level 1 mistakes are not worth spending time on. So don’t let them trick you into it.

Level 2 Mistakes: Death by 1000 cuts

Summary

Just like Level 1, Level 2 mistakes are not a big deal individually. When these mistakes occur, they might cause minor problems, but nothing awful.

The distinction from Level 1 is that Level 2 mistakes add up over time. Eventually, they can grow into significant problems.

Perhaps surprisingly, Level 2 mistakes can have awful results. Happening repeatedly indicates a habit-driven mistake, perhaps even resulting fron behavioral addiction. These can be some of the most problematic problems to resolve as they are highly resistant to change.

Example

You overeat at a meal Overeating for one meal is not a big deal. You might feel ill, but you’ll recover soon. However, you put your health at serious risk if you regularly overeat for many years.

Awareness

Because Level 2 mistakes can seem insignificant individually, they’re easy to ignore or miss entirely. Deliberately considering which Level 2 mistakes you might be making regularly is fundamental to your long-term growth.

Investment

Since Level 2 mistakes add up, you need to understand the accumulated impact to understand what size your effort should be. Your energy spent on this fix should be based on the accumulated impact.

Level 2 mistakes that could roll up into a Level 3 or 4 mistake are, obviously, worthy of tremendous attention.

On the other hand, Level 2 mistakes that just roll up into a slightly more significant Level 2 issue may not be worth a lot of your time.

Level 3 Mistakes: Major Pain

Summary

Level 3 mistakes are much worse than Level 2.

If you’re making Level 3 mistakes more than once or twice at work, you’re going to get a talking to — at a minimum.

Example

A SaaS software engineer accidentally takes down a critical high-traffic production service.

Does it ever happen? Sure, not the end of the world (that would be in Level 4). But if a Level 3 mistake happens multiple times, something is very wrong.

Awareness

You’re likely aware of many of these potential mistakes. A lot of advice (written by bloggers or spoken by grandparents) addresses these typically high-visibility issues. However, some of them can sneak up on you.

Perhaps the software engineer tested on their own machine. It wasn’t until the change was deployed to production that it broke. The mistake was actually made earlier when testing was set up. This mistake went under the radar until much later, when this new code change triggered it.

You have to be vigilant to look for these stealth mistakes and aim to catch them before they happen.

Investment

The Level 3 mistakes that are common knowledge are things you’ve probably already invested in avoiding. Now is the time if you know of any that you haven’t accounted for. That 401k isn’t going to fund itself.

When you make a Level 3 mistake that you didn’t see coming, you need to invest considerable time in keeping it from happening again.

For example, you go to the gas station well before your car runs out of gas. If you run out of gas once, you should think about what went wrong — maybe you had a good reason. If it happens twice, you’ve got a severe problem.

Level 4 Mistakes: This is the end

Summary

A Level 4 mistake means the end, or nearly. Depending on the scope, it might mean the end of your business, career, etc.

Example

A professional writer is caught plagiarizing.

Their career might survive the ordeal or might not, but it would be a disaster.

Awareness

You’re probably aware of most of the potential Level 4 mistakes applicable to your life because they are so obviously terrible that they are considered common sense or addressed by warnings.

For example, a confusing highway junction where someone might enter onto the exit ramp accidentally will be labeled with large "DO NOT ENTER" and "WRONG WAY" signs.

When a new potential Level 4 mistake arises, it tends to make the news (e.g., reducing gatherings and wearing a mask reduces your chances of getting COVID).

Investment

Obviously, these mistakes are worthy of massive investment. Do whatever it takes to identify and avoid these.

Level Summary

Now that you have guideposts for understanding the severity of a mistake, use them to determine how much time and effort to invest in ensuring that this type of accident doesn’t happen again.

Rule 7: Mistakes are a learning opportunity, then they are baggage

When we make a big mistake, we often can’t stop thinking about it.

The stress and anxiety associated with the incident can wake us up in the middle of the night and keep us awake for hours. Replaying the mistake over and over in our minds. Considering what we might have done differently. Worrying about the consequences.

In fact, this is almost precisely what we should be doing — just maybe not in the middle of the night.

Processing our mistakes can be painful, but it is crucial. The potential opportunity to learn and improve from a mistake is enormous. Meanwhile, ignoring the issue can lead to disaster.

The problem is when we try to process a mistake without a structured approach.

The right set of prompts or questions can ensure that our efforts are productive and not just self-flagellation. By asking for specific answers, we move past the general anxiety and focus on the information we need to understand what happened and what to look for next time.

An example mistake processing framework:

- Be precise about what went wrong and what part of it, if any, was under your control

- Determine the Mistake Level and the appropriate level of investment — if unworthy of effort, stop here

- Understand which consequences you can mitigate or resolve immediately and how (and then do so)

- Consider a timeline of what happened, when different corrective actions might have been taken, and which would have been effective in preventing the mistake

- Articulate how you will identify this mistake before it approaches in the future and/or prevent this mistake from happening again

As you practice, you can adjust these or develop your own list of questions that work best for you.

Goldfishing

Once you’ve processed a mistake, learned all you can, and begun to take action on your plan, you’ve wrung all the value you can from the mistake. At this point, it’s time to let go. This is easier said than done, obviously, but is vital to your mental health. Processing the mistake through a framework can be a start.

Another powerful tactic is talking through your situation with someone you trust: a friend, manager, advisor, or therapist.

In the words of Ted Lasso, “You know what the happiest animal on earth is? It’s a goldfish. You know why? Got a 10-second memory.”

Conclusion

Mistakes are a part of life. Breaking down how to think about mistakes can help us process them correctly and grow accordingly.

To make mistakes easier to process, we’ve covered why it’s essential to accept that mistakes happen, how to respond to them, when to invest in avoiding them, and how to learn from them and then let go.

How do you deal with mistakes you’ve made? Let me know 👇